Posted in: Aha! Blog > Great Minds Geodes Blog > Geodes knowledge building > Phonics and Decoding: Building Knowledge with a Phonics Approach to Reading

From the very first page of their very first book, every reader should build knowledge of the world around them while practicing foundational skills.

Geodes® books do just this, creating a new generation of lifelong learners. Learn how phonics-based reading can help emerging readers build knowledge.

One of the oddest grammatically correct sentences in American English goes like this:

Buffalo buffalo Buffalo buffalo buffalo buffalo Buffalo buffalo.

The sentence hinges on three homophonic and homographic words: Buffalo (a city in New York), buffalo (a plural noun similar to bison) and buffalo (a verb meaning “to bully”). A more comprehensible version might be written “Buffalo bison [whom] Buffalo bison bully [also] bully [other] Buffalo bison.”

You may have found it difficult to parse meaning from either sentence. Maybe you had to read the explanation multiple times or even skipped it out of frustration. For skilled readers, reading comprehension is easy—automatic and nearly instantaneous. It’s only when elements of the skill become tricky or garbled that we realize the complexity of this nearly unconscious process.

How Do Word Recognition and Language Comprehension Work Together?

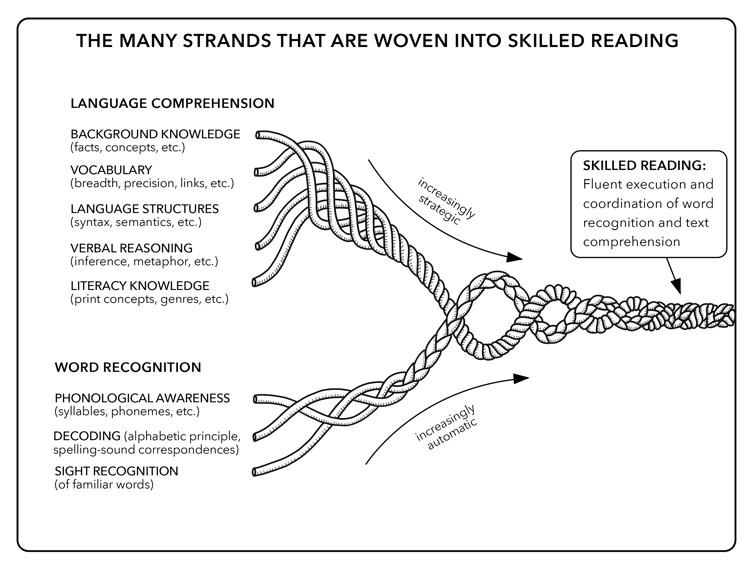

Literary researcher Hollis Scarborough describes reading comprehension as a twin-stranded rope in which each strand is composed of multiple threads.

Image courtesy of Dr. Hollis Scarborough (2001)

To make meaning from text, readers must recognize individual words (the word recognition strand) and understand them in concert (the language comprehension strand). Scarborough suggests that as readers grow in skill, they build automaticity in the word recognition strand and strategic ability in the language comprehension strand. Eventually, all threads become woven tightly into a strong “reading rope.”

A sentence like “Buffalo buffalo Buffalo buffalo buffalo buffalo Buffalo buffalo” wreaks havoc on both strands. It requires background knowledge, vocabulary, and understanding of tricky English language structures such as reduced relative clauses. By using homographs, the sentence also removes phonological variety and creates confusing repetition, making a fluent read-aloud nearly impossible.

Early-grade readers must constantly work at reading comprehension the way you did when you tackled the Buffalo sentence. Specifically, beginning readers devote significant time and energy to the word recognition strand, as the act of recognizing words is not yet automatic for them. During this stage, phonics-aligned reading practice is crucial. As Marilyn Adams writes, citing an earlier study by Connie Juel and Diane Roper: “Ensuring that children’s earliest books are decodable intrinsically rewards them for applying their phonics while reading, from the outset. Moreover, research and theory urge that the benefits of doing so extend well beyond the learning or generalization of any particular letter-sound correspondence” (32–33). In other words, phonics-aligned reading experiences both cement a child’s decoding abilities and demonstrate the value of decoding to the child.

“Ensuring that children’s earliest books are decodable intrinsically rewards them for applying their phonics while reading, from the outset. Moreover, research and theory urge that the benefits of doing so extend well beyond the learning or generalization of any particular letter-sound correspondence” (32–33).

But anyone who has read a variation of “The fat rat sat on the flat mat” knows that decodable texts can feel interminable, robotic, and devoid of meaning. It’s hard to prove the value of the struggle to a reader dragging themselves through stilted sentences and plotless stories. At Great Minds®, we asked: How can we transform the conscious work of reading into a meaningful, even joyful experience?

We decided to make beautiful readable books.

We decided to make Geodes.

What Does Readability Look Like for Emerging Readers?

Readability rests on two central ideas: that the text can be read and that the text is worth reading.

For early-grade students to succeed in reading (rather than guessing or memorizing), text must be controlled for decodability in alignment with an explicit phonics progression. However, text that is too decodable severely limits subject matter. One cannot read about wind turbines if one cannot decode turbine or about cranberry farming without cranberry. There are only so many things to say about cats and pens and balls and cake.

For early-grade students to succeed in reading (rather than guessing or memorizing), text must be controlled for decodability in alignment with an explicit phonics progression. However, text that is too decodable severely limits subject matter.

We designed Geodes to be both accessible and enriching so that students can simultaneously learn to read and read to learn. The text of each Geodes book is controlled so that at least 80 percent of words are decodable—specifically, students are taught phonetic elements and trick words as laid out in Fundations®, the foundational skills program by Wilson Language Training®. The remaining nondecodable words are selected just as intentionally as the decodable and trick words. First and foremost, a 20 percent allowance for nondecodable language provides enormous flexibility for presenting rich subject matter with specificity and precision. In a book about cranberry farming, the author can use content vocabulary like vines, machine, juice, and of course cranberries. Certain nondecodable words, such as survive, harvest, and winter, are even reused across text sets to provide connection and reinforcement of the module’s content vocabulary. And after we scrutinized and justified all nondecodable words, we made deliberate readability-enhancing decisions on sentence, paragraph, and whole book levels. We tracked sentence length, pattern, and complexity. We chose grade-appropriate fonts and used page layout to support the print concepts progression in Fundations®.

Look inside a Geodes with a free digital preview.

How Does Phonics-Based Reading Drive Curiosity, Surprise, and Delight?

Beyond accessibility and even enrichment, readability enthralls the reader. There’s a reason why bestselling thriller novels are often labeled “compulsively readable” in ad copy; we all know the feeling of wanting more episodes of our favorite stories, more information on our favorite subjects. Great Minds wants students to come away from Geodes books with that “more, please!” feeling. We reviewed the module topics of our English language arts curriculum, Wit & Wisdom®, and selected related subtopics that surprise or inspire us, that drive our curiosity and delight. Using poetry and prose, illustrations and photographs, we’ve created a balance of literary and informational texts. Then, we’ve grouped them by topic into knowledge-building sets so that students can deepen their understanding of that topic as they explore. In every book, we include a More section that covers a dovetailing subject, and in some we include backmatter such as recipes, extra photos, or maps.

That said, the goal of Geodes is to drive such curiosity and delight in students that they want even more—more reading, more knowledge, more joy. We hope they exhaust their families with facts about butterflies and birdwatching. We hope they brim with questions about hieroglyphs and the Sydney Opera House. We hope they march to the library for everything they can find on mud mosques, or Pelé, or the Pony Express.

Or even, dare we say, buffalo.

Because yes, there’s a Geodes book for that too.*

*the plural noun, not the city or the verb.

Adams, Marilyn Jager. “Decodable Text: Why, When, and How?” Finding the Right Texts: What Works for Beginning and Struggling Readers, edited by Elfrieda H. Hiebert and Misty Sailors, The Guilford Press, 2009, pp. 23–46.

Scarborough, Hollis S. “Connecting Early Language and Literacy to Later Reading (Dis)abilities: Evidence, Theory, and Practice.” Handbook for Research in Early Literacy. Edited by Susan Neuman and David Dickinson, The Guilford Press, 2001, pp. 97–110.

Download the Article as a Free PDF

Great Minds

Great Minds PBC is a public benefit corporation and a subsidiary of Great Minds, a nonprofit organization. A group of education leaders founded Great Minds® in 2007 to advocate for a more content-rich, comprehensive education for all children. In pursuit of that mission, Great Minds brings together teachers and scholars to create exemplary instructional materials that provide joyful rigor to learning, spark and reward curiosity, and impart knowledge with equal parts delight.

Topics: Geodes knowledge building