Posted in: Aha! Blog > Wit & Wisdom Blog > Fine Art > Artists Make Art

For this second interview in our Author/Illustrator blog series, we enjoyed an enlightening conversation with Melissa Sweet, illustrator of one of our core texts—A River of Words: The Story of William Carlos Williams, by Jen Bryant. In this Caldecott Award Honor Book presented in the module Artists Make Art, Grade 3 students encounter the adventures and imagery of an iconic poet as they build their knowledge about how artists make art and what characterizes and inspires an artist.

Wit & Wisdom teaches reading, writing, language, and speaking and listening skills through authentic, diverse texts. Students notice and wonder about, organize, reveal, and distill information and ideas by examining rich text and vibrant visuals. In the elementary grades, many of the visuals with which students engage are text illustrations.

Trish Huerster, Wit & Wisdom teacher–writer, sat down with Melissa Sweet to discuss the artistic process, the role of illustrations in text and in the classroom, and the life and innovative work of William Carlos Williams.

Huerster: How would you define an artist? What is an artist to you?

Sweet: I think an artist is someone who does something creative within the arts—painting, dance, music, environmental art—or the craftsperson making something utilitarian. Artists are people who have ideas, and who are compelled to create using imagination and know-how.

People who make art don’t always think of themselves as “real Artists,” with a capital ‘A.’ Are there any qualities that you think separate out somebody as an Artist?

I think maybe an Artist with a capital ‘A’ is someone who can't not make something. That is what we live to do; we wake up in the morning wanting to discover and try something, and maybe we fail. An artist is someone who fails a lot. When you’re making something, there can be a lot of false starts. You can call it a mistake, or call it a prototype, but each time you get closer and closer—and eventually you end up with a product. Ever since I was a little kid, I had an entrepreneurial spirit in making art. Artists make something, but they also must sell it. You can’t hang onto something and make a living from it.

That’s something that’s so interesting about William Carlos Williams—that he was a doctor as well as a poet.

Exactly. He's a wonderful example because he had a vocation and avocation. I believe he was someone who, in the definition of an artist, could not stop himself from making poetry. Poetry was part of who he was. I believe it colored who he was as a doctor and how he saw the world. Williams wrote poems about small moments, about seeing something at a glance. His office was attached to his home in Rutherford, New Jersey, but he also traveled making house calls to people of all incomes and walks of life. I think he saw a lot of poverty. He saw a lot of life.

Williams was brilliant at noticing and paying attention, which clearly inspired his work. In the poem “The Red Wheelbarrow” I had the impression (and maybe I read this somewhere) that he was making a house call when he saw that red wheelbarrow. That image brings up so many questions: Who were these people? Why did they have chickens? Where was it? In the middle of a city, maybe? It’s interesting, not knowing exactly where he saw that or what he was thinking. It doesn't really matter. What matters is that he took the time to jot the poem down.

Was there anything that stood out to you or surprised you about William Carlos Williams in your research?

When I was offered the book, I thought, “Those are big shoes to fill. How do you craft a book honoring who he was?” I knew I had to shake it up and find clues to help me figure out what to draw. I went to the Rutherford Public Library where there was a room set aside with Williams’s typewriter, his bowler hat, his papers, and prescription pads. I walked by his house several times with my sketch pad. There was something about going there that made a gigantic difference. I understand now, too, why teachers and librarians talk about primary sources. To see his typewriter and the accouterments of his life was totally different than seeing a photograph of them.

In my research, I also kept coming back to how Williams was inspired by the 1913 Armory Show. The art was out of this world. Talk about risk-taking. Nobody had seen anything like that modern art. I believe Williams wanted to make poetry feel like that.

How did you decide which artistic medium to use? What was your thinking process?

At that time, my local library was having an altered book project. The community was invited to make a piece of art from old books that were slated for the landfill. I had a bunch of old books in my studio, and I was noticing how beautiful the endpapers* were. I started painting on them as if they were a canvas, and suddenly I hit on it: that for me was William Carlos Williams. I thought he would have taken a similar artistic risk. The art began to feel as exciting as his poetry feels when you read it for the first time.

One of the first pictures of Williams—the one of him lying on his back by the river—was painted on the endpapers from an old book. I painted on top of that flower pattern with watercolors and gouache (an opaque water medium). That painting took me about fifteen minutes, but I knew I nailed it. The material provided the starting point. Not everything comes that easy, but this time it did.

But then there was something else, and it played a big part. Jen [Bryant] had inserted Williams’s poems throughout the book. I wasn't feeling that I had captured him and the energy behind him. So, for fun, I illustrated one of his poems in collage, with hand-lettering. The minute I did that, I knew the poems would be the inspiration for the illustrations. That was it. The poems became like a hinge into Williams’s life. They reflected more about William Carlos Williams than my paintings alone, and they allowed me a lot of freedom as the illustrator.

How do you think these illustrations help tell Williams’s story?

When it was agreed that I would illustrate the poems, that text was removed from the manuscript and we had the poems printed on the endpapers. I think the poems became more important visually.

These poems are powerful. They are beautifully crafted pieces about a moment in time—the sparrows, the wheelbarrow, etc. I think they make me see the world differently looking out at my backyard. What do I see? What is the bird that I would notice out there? What strikes me? I think Williams’s poetry wakes us up a little bit with the imagery it creates. The kind of poetry he wrote is accessible. It’s different from a sonnet or a rhyme. His poems are a moment in time. I think he was creating something new and exciting.

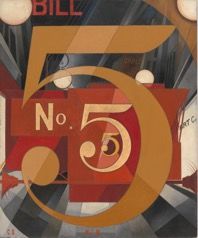

We know that some artists were inspired by William Carlos Williams, such as Charles Demuth, who painted I Saw the Figure 5 in Gold. Can you tell us a little bit about the connection between Demuth’s painting and Williams’s poem “The Great Figure”?

I believe Williams was in New York City in the evening, and he was going to another artist’s studio. A fire truck went by, and he turned his head and jotted the poem down. Years later, when Demuth made the painting based on Williams’s poem, he added a little tiny ‘WCW’ in it. That would be a very cool thing to show students to see what they notice about that.

Students discuss the Demuth painting in depth when they study the module. They spend a lot of time with the details of that painting. Do you have a favorite illustration in the book, one that was the most fun?

I like a lot of the illustrations for different reasons, but the one of Williams by the river was kind of a pivotal point. I could let go and trust that I could just take this risk and go for it. After doing quite a few pieces, with each piece getting kind of wilder, I just let go. If this art wasn’t going to be well received, I didn't care because I was having the time of my life.

Why do you think it's important for students in school today to know about William Carlos Williams?

Williams was pivotal because he invented something new. He is also a great example of someone who chose to have a profession as well as being an artist. When we learn of someone’s successes, and especially when we find their struggles, it humanizes them. I always want kids to come away from one of my biographies to say, “I could do that,” or “I'm like that,” or “I have a similar quirky way of interpreting the world.” We all have our own unique self-expression, and it’s worth pursuing.

Do you have any fun, new projects coming up soon?

I'm working on a book now illustrating a poem by Kwame Alexander called “How to Read a Book.” You know, how does it feel to read a book?

We’re looking forward to seeing that! His book The Crossover is featured in our Grade 8 module The Poetics and Power of Storytelling. Students love it.

I bet they do. I'm really in the spirit of it. It's different, and it's fun. The books I illustrate are all so divergent that I always think, “Oh, this is the perfect book for me right now.” I feel very lucky.

Biography

Melissa Sweet is a Caldecott Honor Book and New York Times Best Illustrated Children’s Book winning illustrator and author. Sweet has illustrated more than one hundred books, including three books by author Jen Bryant — A River of Words: The Story of William Carlos Williams; The Right Word: Roget and His Thesaurus; and A Splash of Red: The Life and Art of Horace Pippin. Sweet's more recent book, Some Writer!: The Story of E. B. White, was a New York Times bestseller and garnered an NCTE Orbis Pictus Award.

*Endpapers are sheets of paper that are pasted flat on the inside of a book—between the front and back covers and first and last pages. They sometimes have textures and patterns.

This interview has been edited for clarity and concision.

Works Referenced

Bryant, Jen. A River of Words: The Story of William Carlos Williams. Illustrated by Melissa Sweet, Eerdmans Books for Young Readers, 2008.

Demuth, Charles. I Saw the Figure 5 in Gold. 1928. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. The Met, Web. Accessed 6 Dec. 2016.

“William Carlos Williams.” Poets.org, Academy of American Poets, Web. Accessed 6 Dec. 2016.

Submit the Form to Print

Great Minds

Great Minds PBC is a public benefit corporation and a subsidiary of Great Minds, a nonprofit organization. A group of education leaders founded Great Minds® in 2007 to advocate for a more content-rich, comprehensive education for all children. In pursuit of that mission, Great Minds brings together teachers and scholars to create exemplary instructional materials that provide joyful rigor to learning, spark and reward curiosity, and impart knowledge with equal parts delight.

Topics: Fine Art