Posted in: Aha! Blog > Wit & Wisdom Blog > Science of Reading > Examining Scarborough’s Rope: Background Knowledge

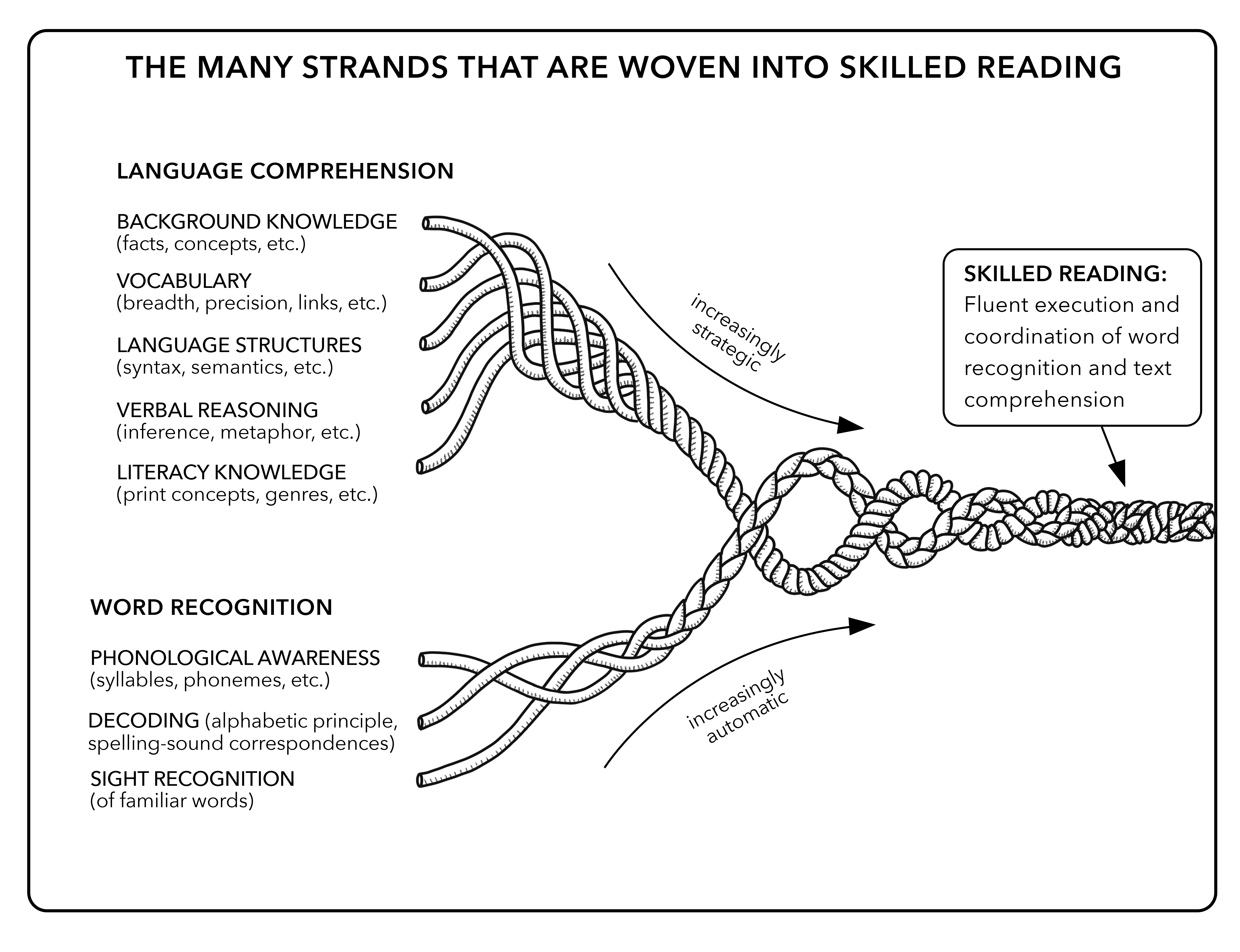

Scarborough’s Reading Rope provides a model for understanding the components of skilled reading. This blog series examines each of the strands of the Language Comprehension half of the rope and how Wit & Wisdom® strengthens these upper strands.

Image courtesy of Dr. Hollis Scarborough, 2001.

The uppermost strand of Language Comprehension represents background knowledge. When a reader knows a lot about a topic, that background knowledge strengthens their comprehension of the text.

Students bring prior knowledge to school, including their cultural experiences and practices, exposure to related content, and previous instruction. As students learn, their prior knowledge grows. It is important to note that students’ prior knowledge may be incomplete or include misconceptions.

Students bring a diversity of prior knowledge to school. English language arts curricula should strategically select, sequence, and repeat key topics and ideas to help students build specific background knowledge for reading. Building background knowledge ensures all students can access new content, regardless of the depth or accuracy of prior knowledge.

Today’s background knowledge is tomorrow’s prior knowledge—once students develop their thinking and commit their knowledge to long-term memory.

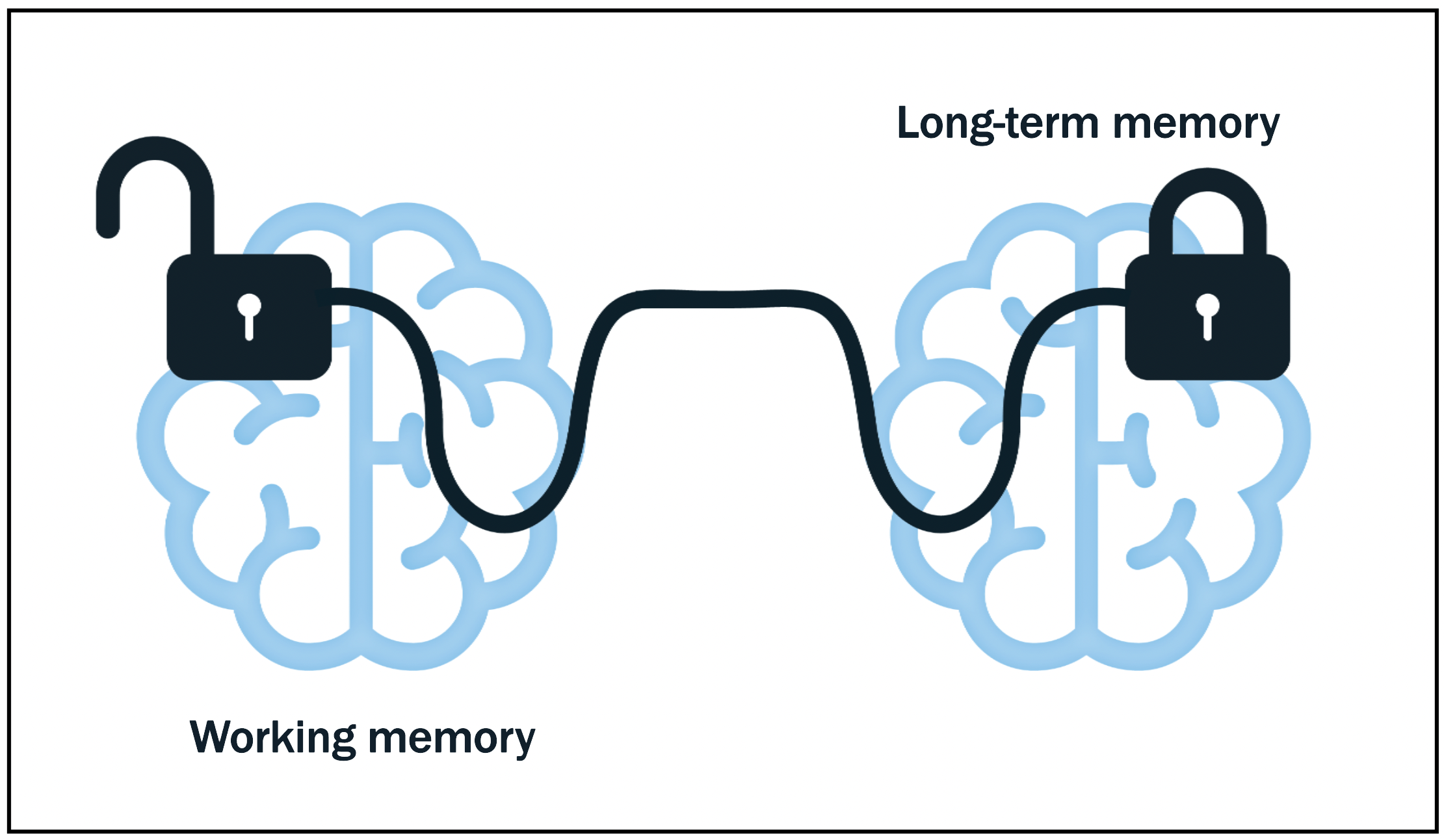

Building Knowledge: A Task for Long-Term Memory

Reading texts without background knowledge is a challenging endeavor. Strategically building background knowledge before reading prepares the student for learning from the text. Cognitive load theory can help explain how knowledge building supports reading texts about unfamiliar topics.

The goal of learning is to store information in long-term memory, but first, students process new ideas, concepts, and skills in their working memory. Students must actively engage in a mental task that commits their learning to memory to move this learning from working memory to long-term memory (Willingham 2008–09, 20). Students need opportunities to work with new knowledge and skills after an introduction to those ideas and later when that learning is less fresh (Sealy 2019).

The goal of learning is to store information in long-term memory, but first, students process new ideas, concepts, and skills in their working memory. Students must actively engage in a mental task that commits their learning to memory to move this learning from working memory to long-term memory (Willingham 2008–09, 20). Students need opportunities to work with new knowledge and skills after an introduction to those ideas and later when that learning is less fresh (Sealy 2019).

The working memory has a limited ability to hold information. The working memory facilitates making connections between new information and prior knowledge, but that capacity is limited. Too many new ideas or skills at once can overtax the working memory, reducing the quality of what the brain can store in the long-term memory.

Long-term memory is better able to hold information, which students can use to make sense of their reading and learning. Deep, lasting knowledge has a home in long-term memory.

The Role of Knowledge in Reading

Cognitive scientists have identified several benefits of background knowledge to readers. We discuss three of these benefits below.

Background knowledge supports recall and summarization. Let’s use Recht and Leslie’s baseball study to understand the difference background knowledge makes for a reader. Students with high levels of prior knowledge about baseball could accurately summarize the events of an inning of baseball, even when those students were low-ability readers. Students with little prior knowledge struggled to recall events accurately.

The high-knowledge students could recall information about baseball stored in their long-term memory and performed well on the recall task. Cognitive scientist Daniel Willingham attributes this to the high-knowledge readers’ ability to “chunk” several actions together to recall a double play rather than multiple events (2006). This ability to “chunk” reduces the students’ cognitive load, allowing them to use more of their working memory to make sense of the relationships between the events.

Background knowledge provides focus and organization to the reader. Without sufficient knowledge, readers can struggle to comprehend the key ideas of texts. In The Knowledge Gap, Natalie Wexler explains that knowledge is like Velcro, which “sticks best to other related knowledge” (33). With background knowledge, readers have an organizing framework they can stick new information onto as they read—a kind of fast-track to long-term memory storage.

Informational texts can be incredibly challenging for students with limited knowledge of a topic. For example, a 2015 released test item from the PARCC assessment includes a passage about how animals keep warm in the Arctic. Having some knowledge of habitats and animal adaptations can help students organize their understanding of the passage. Otherwise, a reader may travel down “blind alleys” that disrupt the coherence of a text—focusing too closely on just one animal or adaptation and losing the author’s main idea (Catts). Sufficient background knowledge helps the reader determine what is and is not valuable information as they read.

Background knowledge strengthens thinking. Knowledge provides the foundation for higher-order thinking skills such as analyzing, synthesizing, and evaluating (Willingham 2006). The more knowledge a reader has stored in their long-term memory about a topic, the more space they have in their working memory. Freeing space in working memory allows a reader to form relationships between ideas and ask questions. Building strong, strategic stores of background knowledge creates an efficient path to critical thinking.

Background Knowledge in Wit & Wisdom

Since all students enter the classroom with a variety of prior knowledge and experiences, English language arts curricula must provide a level playing field by building relevant background knowledge. How does Wit & Wisdom help students build the knowledge they need for future learning?

- Modules prioritize in-depth knowledge of a topic. At Great Minds®, our Humanities team knows the benefits of having knowledge stored in long-term memory. Building that knowledge takes time. Modules typically last for eight to nine weeks to ensure students have sufficient time to build a depth of knowledge of the topic and the literacy knowledge they need to engage in module tasks. Modules provide opportunities for students to revisit key concepts, which helps move new knowledge from working memory to long-term storage.

- Inquiry focuses the knowledge building. An Essential Question guides learning throughout every module. Each lesson includes a Focusing Question and a daily Content Framing Question. This inquiry structure provides a scaffold for students to focus their learning on key ideas, facts, and concepts and avoid the “blind alleys” that readers often go down when reading about unfamiliar topics.

- Instructional routines engage students in actively building knowledge. Thinking is messy, challenging, and collaborative work. Students benefit from regular academic conversation with their peers through the instructional routines in Wit & Wisdom, such as Think–Pair–Share, Tableau, and Gallery Walks. Students engage in the same instructional routines throughout their Wit & Wisdom instruction years. As a result, there are fewer demands on students’ working memory to process directions. Instead, they use their working memory to engage in deeper thinking and active learning.

Wit & Wisdom strategically builds background knowledge over time, beginning in kindergarten. Over the years, students rely on this knowledge to make connections, ask thought-provoking questions, and read with depth and curiosity. Students conclude each module with more substantial prior knowledge for their future endeavors—ensuring all students grow to be knowledge-rich.

For more advice on joyfully building knowledge in Wit & Wisdom, read “Knowledge for All: Strategies for Hosting an Inclusive Knowledge Party” by Wit & Wisdom fellow Julia Sawyer-Wood.

Works Cited

2015 Released Items: Grade 3 Performance-Based Assessment Research Simulation Task. New Meridian, 2019, https://resources.newmeridiancorp.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/3rd_Grade_Research_Simulation_Task_Item_Set_12016.pdf.

Catts, Hugh W. “Rethinking How to Promote Reading Comprehension.” American Educator, Winter 2021–2022, https://www.aft.org/ae/winter2021-2022/catts.

Cervetti, Gina and Elfrieda Hiebert. “Knowledge at the Center of English/Language Arts Instruction.” The Reading Teacher, vol. 72, no. 4, 26 Sept. 2018, pp. 499–507, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/327908045_Knowledge_at_the_Center_of_English_Language_Arts_Instruction.

Recht, Donna R., and Lauren Leslie. “Effect of Prior Knowledge on Good and Poor Readers’ Memory of Text.” Journal of Educational Psychology, vol. 80, no. 1, 1988, pp. 16–20, https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.80.1.16.

Scarborough, Hollis S. “Connecting Early Language and Literacy to Later Reading (Dis)Abilities: Evidence, Theory, and Practice.” Handbook of Early Literacy Research, edited by Susan B. Neuman and David K. Dickinson, Guilford Press, 2001, pp. 97–110.

Sealy, Clare. “The Best Way to Help Children Remember Things? Not ‘Memorable Experiences.’” Education Next, 26 Sept. 2019, https://www.educationnext.org/best-way-to-help-children-remember-things-not-memorable-experiences-excerpt/.

“The Baseball Study by Recht and Leslie.” 5 Aug. 2015, video, 3:50, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qP6qpSrr3cg.

Willingham, Daniel T. “How Knowledge Helps: It Speeds and Strengthens Reading Comprehension, Learning—and Thinking.” American Educator, Spring 2006, http://witeng.link/0869.

Willingham, Daniel T. “What Will Improve a Student’s Memory?” American Educator, Winter 2008–2009, https://www.aft.org/sites/default/files/willingham_0.pdf.

Wexler, Natalie. The Knowledge Gap: The Hidden Cause of America’s Broken Education System—And How to Fix It. New York: Avery, 2019.

About Hannah Dieter

Hannah Dieter is a director of implementation services on the Humanities team at Great Minds. In this role, she leads a team of implementation leaders who support schools and districts across the country with their implementation of Wit & Wisdom and Geodes. Before joining the Great Minds team, she was the director of early childhood education for Lorain City Schools in Ohio. Hannah is also a former kindergarten teacher and instructional coach. She is currently working on her master’s degree in reading science from Mount St. Joseph University in Cincinnati.

About Tanisha Washington

Tanisha Washington is a director of implementation services on the Humanities team at Great Minds. In this role, she leads a team of implementation leaders who support schools and districts across the country with their implementation of Wit & Wisdom and Geodes. Before joining the Great Minds team, she was an assistant principal for a charter school in Washington, DC. As an assistant principal, Tanisha was a member of the 2013 New Leaders’ Aspiring Principals program, the 2018 Relay Graduate School of Education’s National Principals Academy, and the 2018 School Leader Lab’s leadership cohort. Tanisha is also a former elementary school teacher and has a master’s degree in elementary education from American University in Washington, DC.

Submit the Form to Print

Great Minds

Great Minds PBC is a public benefit corporation and a subsidiary of Great Minds, a nonprofit organization. A group of education leaders founded Great Minds® in 2007 to advocate for a more content-rich, comprehensive education for all children. In pursuit of that mission, Great Minds brings together teachers and scholars to create exemplary instructional materials that provide joyful rigor to learning, spark and reward curiosity, and impart knowledge with equal parts delight.

Topics: Featured Science of Reading