Posted in: Aha! Blog > Wit & Wisdom Blog > Science of Reading > Examining Scarborough’s Rope: Vocabulary

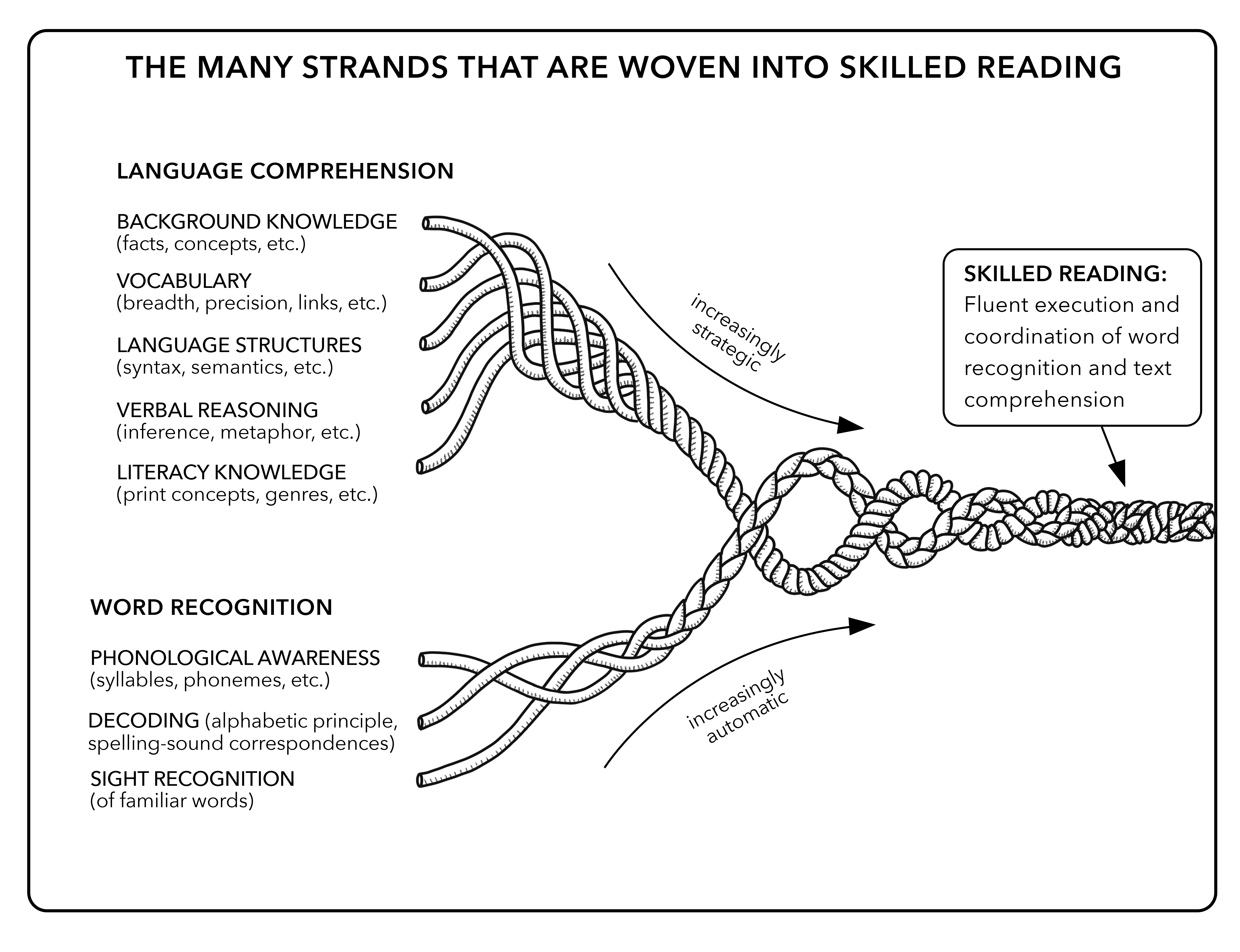

Scarborough’s Reading Rope provides a model for understanding the components of skilled reading. This blog series examines each of the strands of the Language Comprehension half of the rope and how Wit & Wisdom® strengthens these upper strands. Image courtesy of Dr. Hollis Scarborough, 2001.

Image courtesy of Dr. Hollis Scarborough, 2001.

In Scarborough’s Reading Rope, the Vocabulary strand refers to the quantity and quality of a student’s known words. To comprehend challenging texts, students need a wealth of vocabulary knowledge.

Simply put, when students know more words, they can comprehend more of what they read.

Students enter school with a wide range of vocabulary knowledge—presenting a common challenge for educators (Hart and Risley, 7). Gaps between students with limited and extensive vocabulary knowledge often persist throughout their education. But that doesn’t need to be the case. E.D. Hirsch Jr. states that “vocabulary is a plant of slow growth.” When educators use a high-quality curriculum to intentionally support the growth of vocabulary knowledge, they are planting seeds that can close the gap between students.

Growing Vocabulary Knowledge in English Language Arts

Given the word knowledge gap in kindergarten students, schools have a responsibility to grow students’ vocabulary. Most students will be exposed to new words through reading (Cunningham and Stanovich 2–3).

Teachers can increase students’ word knowledge in three research-based ways:

- Use conceptually coherent text sets. A conceptually coherent text set is a group of texts sequenced to build students’ understanding of the deeply related knowledge and concepts within the texts. In a study conducted by Cervetti, Wright, and Hwang, students who read conceptually coherent texts built more knowledge of the texts’ words and related concepts than readers who did not read a conceptually coherent set of texts (773).

- Focus on volume of reading. Volume of reading refers to the amount, quality, and frequency of students’ reading, including classroom texts and independent reading selections. Cunningham and Stanovich draw the conclusion from several of their own studies that once students learn to read, the act of reading is the quickest way to learn new vocabulary because words used in written texts are rarer and more specific than words used in spoken language (1). Engaging students in frequent reading implicitly grows their word knowledge.

- Conduct direct instruction. Providing knowledge-building texts and reading instruction offers a base for developing students’ word knowledge. Teachers should enhance text-focused instruction with direct vocabulary instruction of words that appear in or directly relate to students’ classroom reading (NICHD 4–17).

Wit & Wisdom relies on these three research-based practices to develop word knowledge.

How does Wit & Wisdom build vocabulary knowledge?

All Wit & Wisdom modules include vocabulary instruction. Some vocabulary instruction is implicit as students make meaning out of the texts they encounter. Lessons also employ explicit, direct instruction for important module vocabulary.

Implicit Vocabulary Instruction

- Wit & Wisdom builds on conceptually coherent text sets. Researchers such as Stanovich and Cunningham show that reading is the best way to grow vocabulary. Wit & Wisdom places rich, knowledge-building texts at the center of instruction. Through texts and topics that build coherent knowledge, all students encounter meaning-rich words, often used repeatedly in texts, during Wit & Wisdom instruction.

- Wit & Wisdom offers Volume of Reading (VOR) text lists. Wit & Wisdom provides teachers and families with VOR lists that include many texts that can be found in schools or local libraries. These texts extend the knowledge developed in each module and are excellent selections for students’ independent reading. The module texts and VOR lists offer ample opportunities for implicit vocabulary acquisition. As students repeatedly encounter vocabulary in their reading within the module, they build a stronger understanding of the words in each new context.

Direct Vocabulary Instruction

In Wit & Wisdom, teachers also directly instruct on vocabulary words related to the knowledge students build by reading module texts. Wit & Wisdom provides explicit instruction on words that students will use in their reading, writing, and speaking. These words fall into three categories.

- Content vocabulary includes words that are words that are necessary for understanding a central idea of the domain-specific topic. In Grade 3 Module 1, students learn words such as photosynthesis and nutrient that are content words necessary to understand how sunlight helps sea plants make food in the text Ocean Sunlight: How Tiny Plants Feed the Sea.

- Academic vocabulary consists of high-priority words that can be used across disciplines, will likely be encountered in other texts, are often abstract, and frequently have multiple meanings, which are unlikely to be known by students with limited vocabularies. An example from Grade 3 Module 1 includes academic words such as informational and nonfiction that help students talk about the role the text plays in the module overall.

- Text-critical vocabulary includes words and phrases that are essential to students’ understanding of a particular text or excerpt. During Module 1, Grade 3 students learn text-critical words such as luminous and immense to make meaning in Amos & Boris.

Summary

At all grade levels, students encounter new vocabulary words in their reading, record the words in their vocabulary journals, and use the words in their conversations about the module content. Students are also challenged to use the explicitly taught vocabulary in the module’s speaking and writing tasks.

Vocabulary instruction grounded in knowledge-rich, coherent text sets and volume of reading has the potential to close significant gaps between students who enter school with varying word wealth. When this instruction begins in kindergarten and continues to build throughout students’ education, the slow-growing plant of vocabulary becomes repeatedly fortified. Educators must plant the seeds of vocabulary instruction as early as possible and then care for the steady growth over time of vocabulary knowledge by using a coherent, knowledge-building curriculum.

Works Cited

Cervetti, Gina N., Tanya S. Wright, and HyeJin Hwang. “Conceptual coherence, comprehension, and vocabulary acquisition: A knowledge effect?” Reading and Writing, vol. 29, no. 4, Apr 2016, pp. 761–779. SpringerLink, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-016-9628-x.

Cunningham, Anne E., and Keith E. Stanovich. “What Reading Does for The Mind.” American Educator, American Federation of Teachers, Spring/Summer 1998, https://www.aft.org/sites/default/files/cunningham.pdf.

Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, NIH, DHHS. (2000). Report of the National Reading Panel: Teaching Children to Read: Reports of the Subgroups (00-4754). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, https://www.nichd.nih.gov/sites/default/files/publications/pubs/nrp/Documents/report.pdf.

Hart, Betty, and Todd R. Risley. “The Early Catastrophe: The 30 Million Word Gap by Age 3.” American Educator, American Federation of Teachers, Spring 2003, https://www.aft.org/ae/spring2003/hart_risley.

Hirsch, E.D. Jr. “A Wealth of Words: The key to increasing upward mobility is expanding vocabulary.” City Journal, Winter 2013, https://www.city-journal.org/html/wealth-words-13523.html.

Willingham, Daniel T. “How Knowledge Helps: It Speeds and Strengthens Reading Comprehension, Learning—and Thinking.” American Educator, American Federation of Teachers, Spring 2006, http://witeng.link/0869.

About Hannah Dieter

Hannah Dieter is a director of implementation services on the Humanities team at Great Minds. In this role, she leads a team of implementation leaders who support schools and districts across the country with their implementation of Wit & Wisdom and Geodes. Before joining the Great Minds team, she was the director of early childhood education for Lorain City Schools in Ohio. Hannah is also a former kindergarten teacher and instructional coach. She is currently working on her master’s degree in reading science from Mount St. Joseph University in Cincinnati.

About Tanisha Washington

Tanisha Washington is a director of implementation services on the Humanities team at Great Minds. In this role, she leads a team of implementation leaders who support schools and districts across the country with their implementation of Wit & Wisdom and Geodes. Before joining the Great Minds team, she was an assistant principal for a charter school in Washington, DC. As an assistant principal, Tanisha was a member of the 2013 New Leaders’ Aspiring Principals program, the 2018 Relay Graduate School of Education’s National Principals Academy, and the 2018 School Leader Lab’s leadership cohort. Tanisha is also a former elementary school teacher and has a master’s degree in elementary education from American University in Washington, DC.

Submit the Form to Print

Great Minds

Great Minds PBC is a public benefit corporation and a subsidiary of Great Minds, a nonprofit organization. A group of education leaders founded Great Minds® in 2007 to advocate for a more content-rich, comprehensive education for all children. In pursuit of that mission, Great Minds brings together teachers and scholars to create exemplary instructional materials that provide joyful rigor to learning, spark and reward curiosity, and impart knowledge with equal parts delight.

Topics: Featured Science of Reading